- In fields like biotech and life sciences, where speed and precision are critical, after-the-fact data architectures are creating significant risks.

- Saurav Ghosh, a Vice President at Genmab, explained that the industry has reached an inflection point where inaction is now the greatest danger.

- Leaders must build real-time, event-driven systems, adopt an agile "fail fast" mindset, and collaborate with regulators to succeed.

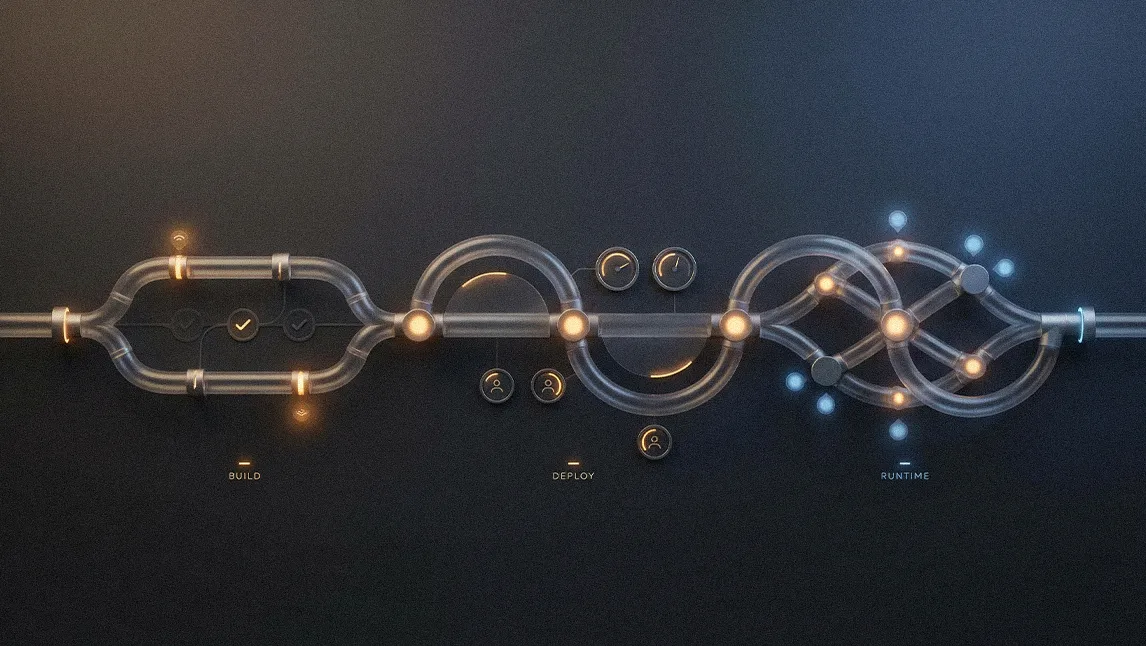

Other sectors might tolerate slow data pipelines, but scientific research and patient care operate in real-time. In industries defined by urgency and precision, every delay is a potential catastrophe. However, most of the infrastructure supporting those operations was designed for after-the-fact analysis. Yet, even as organizations rely on systems never built for speed, many are waiting for the perfect solution to emerge. Meanwhile, the better option for most is real-time, event-driven orchestration.

Already, the industry has reached an inflection point, according to Saurav Ghosh, Vice President of Enterprise Digital Solutions for Data, Digital & AI at Genmab, an antibody science company. With over two decades of experience transforming life sciences with technology at companies like Infosys, Cognizant, IQVIA, and NNIT, Ghosh has a long history of driving growth and patient-centric outcomes. From his perspective, the most significant risk in life sciences today is inaction.

"Making precision decisions across different systems is difficult with static data sources. In biotech, data must be event-driven and point-in-time," Ghosh said. Because the current web of fragmented systems is obsolete, his philosophy is built on a simple principle: the timing of information is as critical as the information itself. To unlock AI's potential, leaders must create an architecture that acts on data instantly.

For Ghosh, the central challenge stems from what he called a "very messy architecture." Most biotech companies rely on a sprawling, fragile ecosystem of siloed SaaS systems, he explained.

Universal donor: By creating a single, intelligent layer to interact with them, the Model-Controller-Prompter (MCP) route offers one viable path forward. But this power also comes with immense responsibility, Ghosh cautioned. "It comes with risk, because you are giving that layer elevated privilege to go into your systems, understand the data, and bring that context into AI to drive decisions."

According to Ghosh, the solution is a framework of strict guardrails, including prompt firewalls, immutable audit trails, and a human in the loop for oversight. Here, a phased approach to trust is a gradual journey, not a sudden leap.

Assisted evolution: "I'm sure it will get to a point where we have a fully autonomous agent," Ghosh predicted. "But for now, I see a hybrid shadow mode with a human in the loop, trending towards a more fully autonomous state, almost like FSD in a Tesla."

Meanwhile, a cautious but deliberate march toward innovation gives leaner, mid-market biotechs an unexpected edge, Ghosh said. Unburdened by the governance and legacy systems of larger pharmaceutical giants, they can adapt more quickly.

Bench-side agility: To navigate the evolving technology, Ghosh recommended an agile mindset. "Fail fast and fail cheap." For him, the goal is to build some muscle memory and figure out what works without accumulating massive "tech debt."

Scale in silico: Today, AI's democratizing power only amplifies this agility. "What the cloud did, especially during COVID, was bring every company to a similar level playing field," Ghosh continued. "AI is taking it to the next level because you are not restricted in how many agents you can create, unlike how many people you can hire. I think technology is a great thing that's bringing equilibrium across companies of different sizes."

But technology alone is not enough. Instead, true transformation requires a two-front approach, Ghosh said. First, leaders must win over executives with a simple value story that focuses on impact and ROI, not technical jargon. Also important are internal gatekeepers from regulatory, privacy, and quality teams, he explained. Executive approval is meaningless without the support of operational functions that ensure compliance.

Eventually, that collaborative approach must extend beyond company walls to include regulators, Ghosh concluded. However, rather than viewing bodies like the FDA as an obstacle, he framed them as essential partners.

Regulatory symbiosis: The more surprising reality for Ghosh is that most regulators are already on board. "I think we underestimate how the regulators are also embracing this. They're using AI for pharmacovigilance and post-market monitoring, so even within the regulatory bodies, there are now use cases where they are exploring AI."

Ultimately, Ghosh is confident the concept will not be foreign to them. "I'm sure there will be consortia where industry professionals, consulting companies, and regulators will come together to advance this as a practice. They will make sure there are good standards laid out that the industry can follow."

.svg)