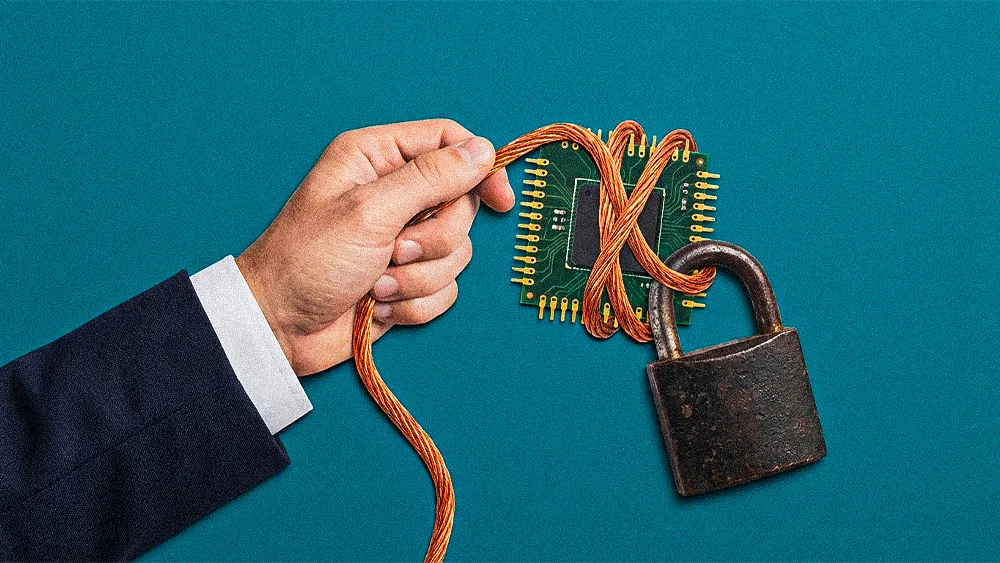

- Major financial institutions are limiting API access to customer data, citing security and cost concerns, which conflicts with fintech innovators' reliance on that data.

- John Pitts from Plaid argued that banks' restrictions are a strategic move to stifle competition and create new revenue streams, similar to credit card fees, not a technical necessity.

- AI will increase the data demand and escalate the battle over control of consumer financial data.

A growing number of enterprises are restricting API access to consumers' own data, citing cost, security, or other strategic concerns. In banking, this trend has drawn scrutiny under the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's (CFPB) Rule 1033 which addresses how major banks limit API access for consumers who want to use third-party applications to access their own data. Two high-profile tech cases of this trend are Salesforce's Slack limiting its API and the Cloudflare and Perplexity scraping dispute, which highlight the growing tension between control and innovation proliferating across industries.

The problem is consumers don't care about the underlying infrastructure. Consumers just want better experiences, like faster payments. The path to that improved experience is predicated on who controls the underlying data. In banking, with the influx of potentially threatening applications like Zelle, Chime, and other more consumer-facing banks, the major banks are those gatekeepers, and they are leaning on obfuscating the technical limitations of APIs as a means of restricting access.

We spoke with John Pitts, the Head of Industry Relations and Digital Trust at Plaid, to set the stage. Having previously served as Deputy Assistant Director at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), Pitts has a unique perspective forged on both sides of the regulatory and innovation divide. To grasp the current conflict, you have to understand the historical mindset of the incumbent banks. For decades, they never saw consumer data as a valuable asset to be leveraged for innovation; they saw it as a toxic liability to be contained.

The Radioactive Waste Mentality: "Financial data is essentially radioactive waste that we have to store. It's not a valuable thing. It's actually a risky thing because we can't do anything with it... our biggest concern is that it would somehow get out. You don't want the leakage of that waste."

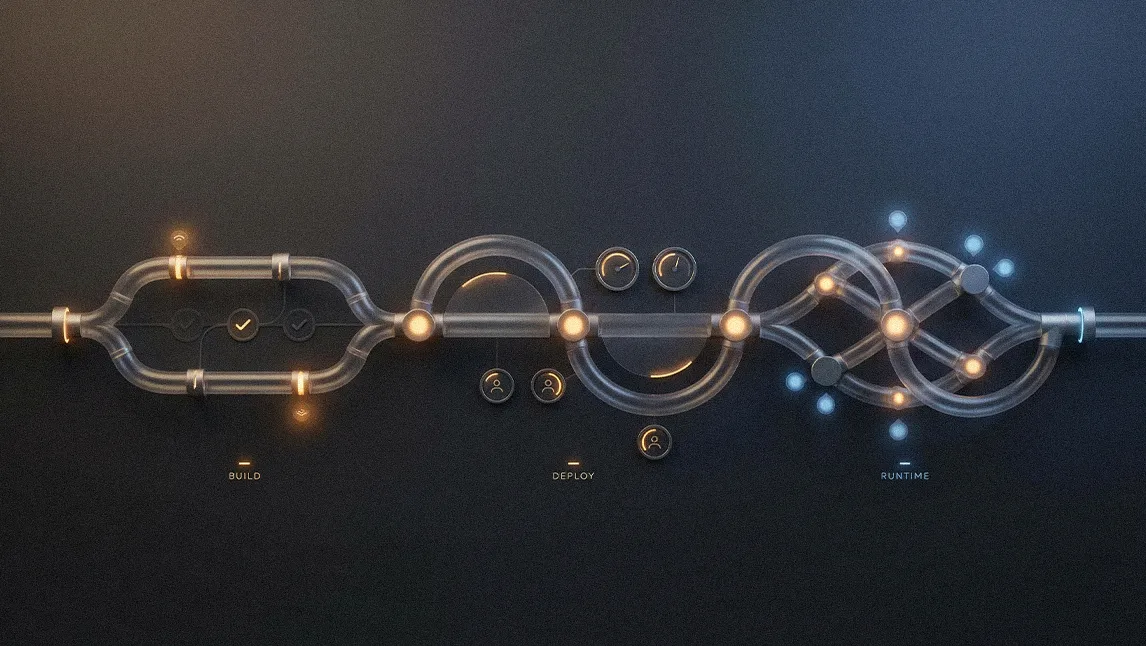

This perspective and posturing meant that innovation had to come from the outside. An early example of this started with companies like Intuit pre-populating tax information—simple automations that made life easier for the user. As FinTech use cases expanded into areas like lending, peer-to-peer payments, and earned wage access, banks grew concerned. Fintechs like Chime, which now has more accounts than any other bank in the United States, emerged as direct competitors. Pitts positioned the bank's perspective bluntly, "Why would they build infrastructure to help competitors grow?" The new complaint is that these APIs are suddenly getting too expensive to maintain, but Pitts argued that while banks may be attempting to fortify their walls, AI was about to render those walls obsolete.

The Checkmate Argument: "You can't change demand. If you try to choke off demand at the API, it is very likely that the extremely low cost of extractors is going to mean that companies just shift to AI-coded extractors. It probably won't be a couple of regulated data aggregators managing it. It will be thousands and thousands of companies hitting your web portal in a way that is very difficult to manage and creates its own substantial cost and risks."

That "cost" argument appears to be a form of strategic misdirection. In an age of commoditized cloud infrastructure, the idea that a multi-trillion-dollar institution is struggling with API overhead seems suspect. Pitts argued the real motive wasn't cost recovery, but a deliberate strategy to create a new revenue stream.

A Strategic Misdirection: "I think that pricing is much more about seeing whether there is an opportunity to generate revenue from a system versus recover costs from a system. It's not a coincidence that payments is one of the areas where the highest focus is on. Payments is something where there are existing models like interchange, where financial institutions are used to thinking of that infrastructure as a revenue source, not a cost recovery source. I think there's an attempt to make non-card payments a new revenue source for financial institutions."

This is strikingly similar to Apple's defense in lawsuits over its App Store. When challenged on the massive profit margins of the App Store, Apple executives claimed they had no idea what the margins were. For a company with famously tight control over its finances to claim ignorance seems like a strategic obfuscation, much like banks claiming not to know the cost of their own APIs.

This entire conflict is about to be supercharged by agentic AI. Pitts used the example of how JPMorgan Chase offers 0.01% interest on deposits while Ally Bank offers around 4%. A consumer theoretically has the ability to switch, but the friction in the system prevents it. In a hypothetical but plausible example, Pitts posed the question, "What if an agentic AI, like a personal version of The Points Guy, could manage your finances effectively?" If all consumers start using agentic AI to help manage their finances, the data demands and volumes will go up dramatically, giving banks even more reason to want to gatekeep access.

The Core Dynamic: "It often requires innovation from outside the banking system to drive innovation within the banking system. It's a race between innovation and distribution. The banks have more distribution than any fintech has. The fintech apps have innovation. Sometimes the innovations will move faster than the distribution, and then they win in the competitive market. Sometimes distribution innovates later, but then with their distribution power, they end up dominating the market."

But this brings the story full circle. The conflict is not a traditional summary, but a final, powerful theme about the perpetual battle between incumbents and innovators. We’ve seen this play out before. Venmo and Cash App existed for years before the banks responded with Zelle. Now, Zelle processes more payments than its competitors by leveraging the banks' massive distribution network. The banks will be cautious with agentic AI, but competitive pressure will eventually drive them to adopt it.

A Race Between Innovation and Distribution: "Never underestimate the quality of banks. They're good at what they do. They've been doing it for hundreds of years."

In the meantime, the outside innovators will drive as much innovation as possible to meet consumer demand where it is today. The fight over API access isn’t about technology. It’s about control, competition, and the future of financial services. Banks hold the distribution power, fintechs drive innovation, and AI is about to tilt the scales. For consumers, the outcome will determine who truly wins: the incumbents protecting their walls or the innovators tearing them down to deliver smarter, faster, and more personalized experiences.

.svg)